On February 27, 2025, in Chabolla v. ClassPass Inc., the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, in a split 2-1 decision, held that website users were not bound by the terms of a “sign-in wrap” agreement.

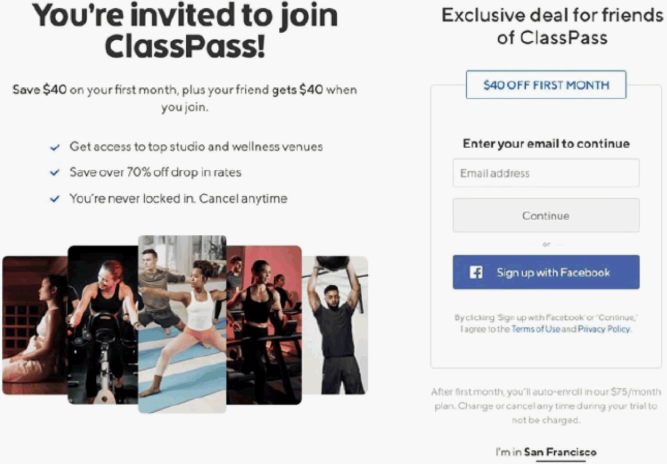

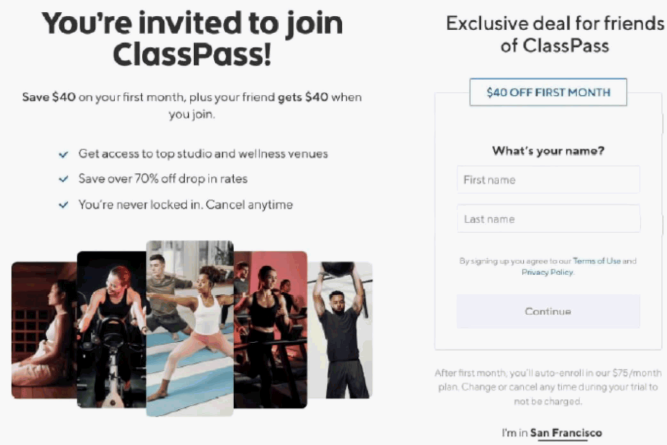

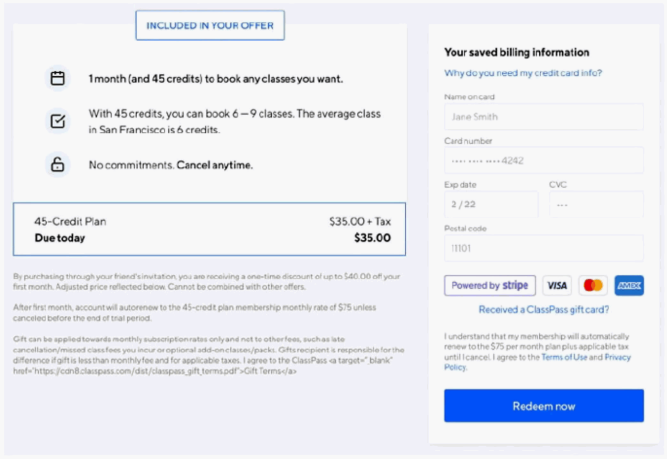

ClassPass sells subscription packages that grant subscribers access to an assortment of gyms, studios and fitness and wellness classes. The website requires visitors to navigate through several webpages to complete the purchase of a subscription. After the landing page, the first screen (“Screen 1”) states: “By clicking ‘Sign up with Facebook’ or ‘Continue,’ I agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.” The next screen (“Screen 2”) states: “By signing up you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.” The final checkout page (“Screen 3”) states: “I agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.” On each screen, the words “Terms of Use” and “Privacy Policy” appeared as blue hyperlinks that took the user to those documents.

The court described four types of Internet contracts based on distinct “assent” mechanisms:

- Browsewrap - users accept a website’s terms merely by browsing the site, although those terms are not always immediately apparent on the screen (courts consistently decline to enforce).

- Clickwrap - the website presents its terms in a “pop-up screen” and users accept them by clicking or checking a box expressly affirming the same (courts routinely enforce).

- Scrollwrap - users must scroll through the terms before the website allows them to click manifesting acceptance (courts usually enforce).

- Sign-in wrap - the website provides a link to the terms and states that some action will bind users but does not require users to actually review those terms (courts often enforce depending on certain factors).

The court analyzed ClassPass’ consent mechanism as a sign-in wrap because its website provided a link to the company’s online terms but did not require users to read them before purchasing a subscription. Accordingly, the court held that user assent required a showing that: (1) the website provides reasonably conspicuous notice of the terms to which users will be bound; and (2) users take some action, such as clicking a button or checking a box, that unambiguously manifests their assent to those terms.

The majority found Screen 1 was not reasonably conspicuous because of the notice’s “distance from relevant action items” and its “placement outside of the user’s natural flow,” and because the font is “timid in both size and color,” “deemphasized by the overall design of the webpage,” and not “prominently displayed.”

The majority did not reach a firm conclusion on whether the notice on Screen 2 and Screen 3 is reasonably conspicuous. On one hand, Screen 2 and Screen 3 placed the notice more centrally, the notice interrupted the natural flow of the action items on Screen 2 (i.e., it was not buried on the bottom of the webpage or placed outside the action box but rather was located directly on top of or below each action button), and users had to move past the notice to continue on Screen 3. On the other hand, the notice appeared as the smallest and grayest text on the screens and the transition between screens was somewhat muddled by language regarding gift cards, which may not be relevant to a user’s transaction; thus, a reasonable user could assume the notice pertained to gift cards and hastily skim past it.

Even if the notice on Screen 2 and Screen 3 was reasonably conspicuous, the majority deemed the notice language on both screens ambiguous. Screen 2 explained that “[b]y signing up you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy,” but there was no “sign up” button—rather, the only button on Screen 2 read “Continue.” Screen 3 read, “I agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy,” and the action button that follows is labeled “Redeem now”; it does not specify the user action that would constitute assent to the terms. In other words, the notice needs to clearly articulate an action by the user that will bind the user to the terms, and there should be no ambiguity that the user has taken such action. For example, clicking a “Place Order” button unambiguously manifests assent if the user is notified that “by making a purchase, you confirm that you agree to our Terms of Use.”

Accordingly, the court held that Screen 1 did not provide reasonably conspicuous notice and, even if Screen 2 and Screen 3 did, progress through those screens did not give rise to an unambiguous manifestation of assent.

The dissent noted that the majority opinion “sows great uncertainty” in the area of internet contracts because “minor differences between websites will yield opposite results.” Similarly, the dissent argued that the majority opinion will “destabilize law and business” because companies cannot predict how courts are going to react from one case to another. Likewise, the dissent expressed concern that the majority opinion will drive websites to the only safe harbors available to them—clickwrap or scrollwrap agreements.

While ClassPass involved user assent to an arbitration provision in the company’s online terms, the issue of user assent runs far deeper, extending to issues like consent to privacy and cookie policies—a formidable defense to claims involving alleged tracking technologies and wiretapping theories. Notwithstanding the majority’s opinion, many businesses’ sign-in wrap agreements will differ from the one at issue in the lawsuit and align more closely with the types of online agreements that courts have enforced. Nonetheless, as the dissent noted, use of a sign-in wrap agreement carries some degree of uncertainty. Scrollwrap and clickwrap agreements continue to afford businesses the most certainty.

Search

Recent Posts

Categories

- Behavioral Advertising

- Centre for Information Policy Leadership

- Children’s Privacy

- Cyber Insurance

- Cybersecurity

- Enforcement

- European Union

- Events

- FCRA

- Financial Privacy

- General

- Health Privacy

- Identity Theft

- Information Security

- International

- Marketing

- Multimedia Resources

- Online Privacy

- Security Breach

- U.S. Federal Law

- U.S. State Law

- Workplace Privacy

Tags

- Aaron Simpson

- Accountability

- Adequacy

- Advertisement

- Advertising

- Age Appropriate Design Code

- American Privacy Rights Act

- Anna Pateraki

- Anonymization

- Anti-terrorism

- APEC

- Apple Inc.

- Argentina

- Arkansas

- Article 29 Working Party

- Artificial Intelligence

- Audit

- Australia

- Austria

- Automated Decisionmaking

- Baltimore

- Bankruptcy

- Behavioral Advertising

- Belgium

- Biden Administration

- Big Data

- Binding Corporate Rules

- Biometric Data

- Blockchain

- Bojana Bellamy

- Brazil

- Brexit

- British Columbia

- Brittany Bacon

- Brussels

- Business Associate Agreement

- BYOD

- California

- CAN-SPAM

- Canada

- Cayman Islands

- CCPA

- CCTV

- Chile

- China

- Chinese Taipei

- Christopher Graham

- CIPA

- Class Action

- Clinical Trial

- Cloud

- Cloud Computing

- CNIL

- Colombia

- Colorado

- Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States

- Commodity Futures Trading Commission

- Compliance

- Computer Fraud and Abuse Act

- Congress

- Connecticut

- Consent

- Consent Order

- Consumer Protection

- Cookies

- COPPA

- Coronavirus/COVID-19

- Council of Europe

- Council of the European Union

- Court of Justice of the European Union

- CPPA

- CPRA

- Credit Monitoring

- Credit Report

- Criminal Law

- Critical Infrastructure

- Croatia

- Cross-Border Data Flow

- Cross-Border Data Transfer

- Cyber Attack

- Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency

- Data Brokers

- Data Controller

- Data Localization

- Data Privacy Framework

- Data Processor

- Data Protection Act

- Data Protection Authority

- Data Protection Impact Assessment

- Data Transfer

- David Dumont

- David Vladeck

- Deceptive Trade Practices

- Delaware

- Denmark

- Department of Commerce

- Department of Health and Human Services

- Department of Homeland Security

- Department of Justice

- Department of the Treasury

- Department of Treasury

- District of Columbia

- Do Not Call

- Do Not Track

- Dobbs

- Dodd-Frank Act

- DORA

- DPIA

- E-Privacy

- E-Privacy Directive

- Ecuador

- Ed Tech

- Edith Ramirez

- Electronic Communications Privacy Act

- Electronic Privacy Information Center

- Electronic Protected Health Information

- Elizabeth Denham

- Employee Monitoring

- Encryption

- ENISA

- EU Data Protection Directive

- EU Member States

- European Commission

- European Data Protection Board

- European Data Protection Supervisor

- European Parliament

- European Union

- Facial Recognition Technology

- FACTA

- Fair Credit Reporting Act

- Fair Information Practice Principles

- Federal Aviation Administration

- Federal Bureau of Investigation

- Federal Communications Commission

- Federal Data Protection Act

- Federal Trade Commission

- FERC

- Financial Data

- FinTech

- Florida

- Food and Drug Administration

- Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act

- France

- Franchise

- Fred Cate

- Freedom of Information Act

- Freedom of Speech

- Fundamental Rights

- GDPR

- Geofencing

- Geolocation

- Geolocation Data

- Georgia

- Germany

- Global Privacy Assembly

- Global Privacy Enforcement Network

- Gramm Leach Bliley Act

- Hacker

- Hawaii

- Health Data

- HIPAA

- HITECH Act

- Hong Kong

- House of Representatives

- Hungary

- Illinois

- India

- Indiana

- Indonesia

- Information Commissioners Office

- Information Sharing

- Insurance Provider

- Internal Revenue Service

- International Association of Privacy Professionals

- International Commissioners Office

- Internet

- Internet of Things

- Iowa

- IP Address

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Jacob Kohnstamm

- Japan

- Jason Beach

- Jay Rockefeller

- Jenna Rode

- Jennifer Stoddart

- Jersey

- Jessica Rich

- John Delionado

- John Edwards

- Kentucky

- Korea

- Latin America

- Laura Leonard

- Law Enforcement

- Lawrence Strickling

- Legislation

- Liability

- Lisa Sotto

- Litigation

- Location-Based Services

- London

- Louisiana

- Madrid Resolution

- Maine

- Malaysia

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Meta

- Mexico

- Microsoft

- Minnesota

- Mobile

- Mobile App

- Mobile Device

- Montana

- Morocco

- MySpace

- Natascha Gerlach

- National Institute of Standards and Technology

- National Labor Relations Board

- National Science and Technology Council

- National Security

- National Security Agency

- National Telecommunications and Information Administration

- Nebraska

- NEDPA

- Netherlands

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- New Zealand

- Nigeria

- Ninth Circuit

- North Carolina

- North Korea

- Norway

- Obama Administration

- OCPA

- OECD

- Office for Civil Rights

- Office of Foreign Assets Control

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Online Behavioral Advertising

- Online Privacy

- Opt-In Consent

- Oregon

- Outsourcing

- Pakistan

- Parental Consent

- Payment Card

- PCI DSS

- Penalty

- Pennsylvania

- Personal Data

- Personal Health Information

- Personal Health Information

- Personal Information

- Personally Identifiable Information

- Peru

- Philippines

- Phyllis Marcus

- Poland

- PRISM

- Privacy By Design

- Privacy Policy

- Privacy Rights

- Privacy Rule

- Privacy Shield

- Profiling

- Protected Health Information

- Ransomware

- Record Retention

- Red Flags Rule

- Rhode Island

- Richard Thomas

- Right to Be Forgotten

- Right to Privacy

- Risk-Based Approach

- Rosemary Jay

- Russia

- Safe Harbor

- Sanctions

- Schrems

- Scott Kimpel

- Securities and Exchange Commission

- Security Rule

- Senate

- Sensitive Data

- Serbia

- Service Provider

- Singapore

- Smart Grid

- Smart Metering

- Social Media

- Social Security Number

- South Africa

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- South Korea

- Spain

- Spyware

- Standard Contractual Clauses

- State Attorneys General

- Steven Haas

- Stick With Security Series

- Stored Communications Act

- Student Data

- Supreme Court

- Surveillance

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Taiwan

- Targeted Advertising

- Telecommunications

- Telemarketing

- Telephone Consumer Protection Act

- Tennessee

- Terry McAuliffe

- Texas

- Text Message

- Thailand

- Transparency

- Transportation Security Administration

- Trump Administration

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Unmanned Aircraft Systems

- Uruguay

- Utah

- Vermont

- Video Privacy Protection Act

- Video Surveillance

- Virginia

- Viviane Reding

- Washington

- Whistleblowing

- Wireless Network

- Wiretap

- ZIP Code